When Elon Musk, outspoken CEO of Tesla and founder of Space X, sensationally warned of an imminent attack by the assassin drones in November 2018, he probably wasn’t expecting that within two months of making another predication about technology overtaking humanity, two unmanned aircraft would ruin Christmas plans for hundreds of thousands of holidaymakers. Of course, the incident was nowhere near as extreme as Musk predicted, but the extent of the impact was felt by many.

Around 1,000 flights were cancelled in December, affecting the travel plans of 140,000 people after two unmanned aircraft hampered London Gatwick Airport ’s operations for two days. Separately, departures at London Heathrow were delayed by several hours in early January after a drone was spotted in the vicinity of the UK’s busiest airport. Speaking to Sky News about the incidents, Chris Grayling, the UK’s transport secretary, said that as technology advances such occurrences are likely to be more frequent.

The last decade has seen a tremendous innovation in technology. Advances have not only improved services and offerings, but also increased accessibility to information. A person with an internet connection in a far remote corner of the world can now obtain the same information as someone working in Silicon Valley and potentially utilise it to make decisions. While this has been a positive development in terms of human and business growth, allowing markets to become truly global, it has also created pitfalls.

In November 2018, police in India arrested more than 20 people on suspicion of defrauding individuals around the world. The complainants were the FBI, Interpol and Microsoft. Only now, years after such cells have been set up, are the legal and regulatory bodies succeeding in finding and stopping such illegal activities. This wouldn’t have happened a decade or two ago. Such fraud is just one example of the pitfalls of fast technological advancement, but there are unintended consequences as well.

Take high-frequency trading for example. Despite the financial sector being heavily regulated, there have been many issues, from the 2010 Flash Crash, Knight Capital losing $440 million in 2012 and more recently, a login glitch at the Tokyo Stock Exchange. There was no mal-intent on the part of the computer, but its actions wiped out 75 per cent of Knight Capital’s equity value within days. The authorities have since come up with stricter regulations in the form of MiFID II (in Europe) to manage these risks, but the question over what algorithms can do remains.

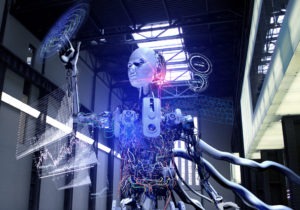

As the growth in the Fintech sector continues, and technologies such as Blockchain, AI and robotics become commonplace in the financial sector, it is prudent to question whether the existing compliance and operational departments have the required skills and tool sets to deal with the fall out. If experience teaches us anything, the answer is no. While large financial institutions themselves have generally been conservative in their adoption of new technologies, they are now facing unprecedented disruption:

Firstly, banks will need to reflect internally and change not only the culture, but also the way people work. The expected increase in automation will reduce the need for as many repetitive jobs, shifting the focus to the workforce’s ability to innovate or disrupt. As millennials join the workforce, this is an opportunity to design organisations, so they are able to adapt to innovation faster and more securely than before. The controls should be predictive in nature and focus on the root of the problem unlike the current end-of-day reconciliations that fix the issue after the fact.

Secondly, banks should work closely with regulatory and legal authorities, as well as their counterparts, to build a framework that is standardised across the globe. The current regulatory requirements comprise a myriad of requests for data in various formats that is not easy to decode for either the firms or the regulators. Simpler outcome-based standards with foundations based on the ‘right’ behaviour will better serve the goals of being compliant.

Thirdly, before adopting new technologies, banks and other organisations need to understand their current data, processes and infrastructure. As an example, a big data solution built on poor quality data is a white elephant that nobody wants to own. In order to conduct a successful digital transformation, banks need not only to understand where they are going, but also where they are now and the path that needs to be traversed.

Like the proverbial sword, disruptive technology, if used incorrectly, can act as a weapon in the wrong hands. Fortunately, with the right behaviour and conduct, it can also be a protective force to herald the move of centuries-old financial institutions into the future. There is no doubt that compliance can’t compete with technological innovation, but it can certainly adopt it. After all, in the case of the incident at Gatwick Airport, it was technology which came to the rescue of the passengers.